Research Update: Child welfare agencies that use more research evidence have higher rates of permanency for children in foster care

Results of the first wave of analysis from the Project on Research Evidence Use by Child Welfare Agencies show that the more often agency staff used research evidence to learn about children in their care, the faster the agency discharged children in foster care to permanency.

Continue reading to learn more about the study, implications for staff development, and avenues for further research.

This study was supported by the W. T. Grant Foundation. Kim DuMont served as our project officer. We are grateful to Dr. Dumont and others at the Foundation for their support and guidance. Lawrence Palinkas, University of Southern California, and Laura Pinsoneault, Alliance for Families and Children, were co-authors. We are grateful for their help at each phase of the project.

OVERVIEW

Research evidence is information that has been generated according to scientific principles and practices. It can be qualitative or quantitative and it can be derived from a variety of sources—SACWIS systems, peer reviewed journals, randomized clinical trials, systematic case record reviews, and program evaluations, just to name a few. The term research evidence use—or REU—refers to how people use that information to make policy and practice decisions. REU includes the way people acquire evidence in the first place, the way they process or interpret it, and the way they apply it to problem solving processes.

Today, child welfare agencies are investing evermore resources into using research evidence to support their decisions. The theory is that when staff use research evidence to inform their policy and practice, they will make more targeted and effective decisions, which in turn will lead to better outcomes for clients. It’s a sensible assumption—yet, one that until now has not been carefully examined.

THE QUESTION

Recently, with support from the W.T. Grant Foundation, the Center for State Child Welfare Data at Chapin Hall initiated the Project on Research Evidence Use by Child Welfare Agencies, a multipart program aimed at understanding and improving the ways child welfare agencies use research evidence to make decisions that affect children and families. In Phase 1 of the analysis, we were interested in how agency staff acquire evidence, specifically the types of evidence that can be derived from electronic records that are increasingly available to public and private agencies, alike. We asked two main questions:

- Are some staff more likely than others to generate this type of research evidence in the course of their work?

- Do agencies that have more research evidence users achieve better permanency outcomes for children in foster care?

THE METHODS

We surveyed executives, mid-level managers, supervisors, and caseworkers at 26 private foster care agencies in a large state, asking them about how often they used electronic records to generate evidence about how well their clients were doing. These items were part of a larger questionnaire that asked staff about other types of REU behavior, as well as about individual and agency characteristics.

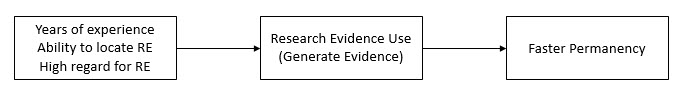

To answer our first research question, we tested whether years of experience, self-reported ability to locate research evidence, and one’s own regard for research evidence influenced individuals’ REU. To answer the second question, we used data from the Multistate Foster Care Data Archive to test whether agencies that had more research evidence users achieved faster permanency for children in care. That analysis accounted for other influences on outcomes such as case mix, care type, and geography.

THE RESULTS

We found that staff who had more years on the job, reported they were able to locate research evidence, and felt that research evidence was a valuable asset to their decision making were more likely to generate research evidence than staff who did not have those characteristics. We also found that agencies with more research evidence users had faster permanency rates than agencies with fewer. Moreover, the results showed that individual staff characteristics, alone, were not associated with the better permanency outcomes—staff had to report using research evidence in order to bring about the better results for children.

THE IMPLICATIONS

This analysis is the first step in a larger effort to understand how REU is related to outcomes for children in care. In future studies we’ll test whether there are agency or other contextual characteristics that shape the relationship. We’ll also explore the role of other REU behaviors. For instance, the analysis described above asked about whether acquiring evidence from electronic records matters, but what about staff’s efforts to get evidence from other sources? What about the way staff interpret evidence, and whether and how they apply it to the decisions that come across their desks?

In the meantime, these initial findings spark a major conversation about staff development and capacity building. If REU is related to better outcomes for children in care, then one critical question is whether REU can be improved through training and technical assistance. The answer to that question will play a powerful role in how agencies allocate resources to promote child and family well-being.

LEARN MORE

To learn more about Phase 1 of the Project on Research Evidence Use by Child Welfare Agencies, read our brief published in the Spring 2016 edition of CW360.

For more detail on the analysis, read a pre-publication summary of the research and the findings.

Interested in improving your staff’s REU skills? Click here for information about Advanced Analytics for Child Welfare Administration, the Data Center’s 5-day seminar on best practices in administrative data analysis and continuous quality improvement.