Interpreting variation: An essential step between identifying the problem and developing the solution

In the previous post, we discussed how observing variation enables you to define the problem that you want to use CQI to improve. Once you have observed that an outcome of interest varies and you have determined that the variation represents a problem that needs to be solved, the next step is to determine how the dynamics of your child welfare system create an environment in which that variation is permitted to emerge. In other words, the next question is: Why does variation exist? Answering this question is essential for obvious reasons; unless you know the cause of your problem you cannot go about devising a solution.

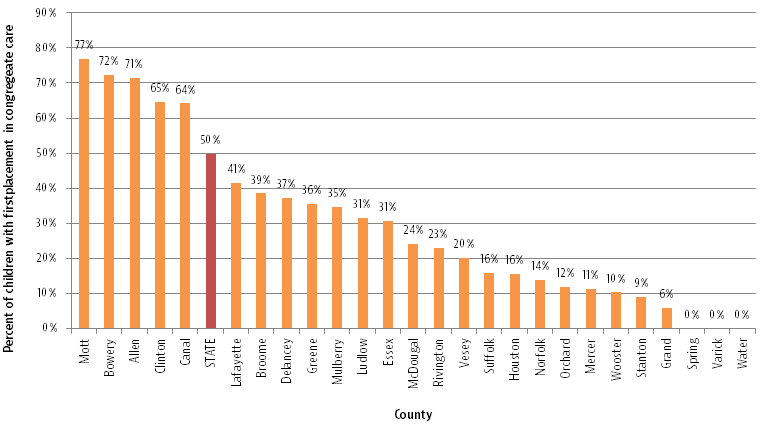

Earlier in this series of posts, we introduced a fictitious state that was concerned about its use of group care for children in foster care. We observed that the counties in that state varied widely on the proportion of children in foster care who experience their first placement in a group setting:

The next CQI question is: Why do some counties use more group care than others? Outcomes can vary for two main reasons:

First, outcomes can vary because of characteristics of children and families, themselves. It may be that in the high-use counties above, children coming into care are more likely to have serious mental health needs that cannot be managed in a family setting. Those counties might argue that group care placement is appropriate because that level of care is required to meet children’s needs. When variation exists because different policies and practices are needed to meet the unique needs of children and families, we want to preserve the heterogeneity of service delivery. Whether group care is the best or only way to meet the needs of children with serious mental health needs is beside the point for the time being. The point here is to note that when a system delivers different care to different groups of children because different groups of children need different kinds of care in order to achieve the same success, the next step from a CQI perspective is to support a nimble system that is prepared to tailor its services. (…and prepared to ask the next question about variation: Why do children in some counties have more mental health needs than in others?)

Outcomes can also vary because jurisdictions differ in the way they treat the same kinds of children. Perhaps there is no county-to-county variability in the mental health needs of children entering care in our sample state, but there is a real difference in each county’s service array. Maybe the variation we observe in group care use is due to the fact that the high-use counties have large emergency shelters and struggle with a lack of foster homes, while the low-use counties have more foster homes and robust protocols for searching for kinship caregivers. In this case, variation in group care use has little to do with differences in children’s needs and more to do with differences in individual counties’ policies and practices. When variation exists because jurisdictions treat the same kinds of children differently—that is, those jurisdictions differ in the process of care, the quality of care, and the resources they devote to delivering care—we want to minimize the heterogeneity of service delivery. In these cases, the next step from a CQI perspective is to identify the policies and practices that bring about the best outcomes and encourage those protocols throughout the system.

Determining how much variation is due to differences in children versus how much is due to differences in service delivery is a complex task, but when that task is left undone, agencies run the risk of developing strategies, initiatives, and interventions that fail to address the sources of the outcomes they are trying to change. The importance of this type of analysis comes into particular focus in the context of the Title IV-E waiver. Click to the next post to read how.